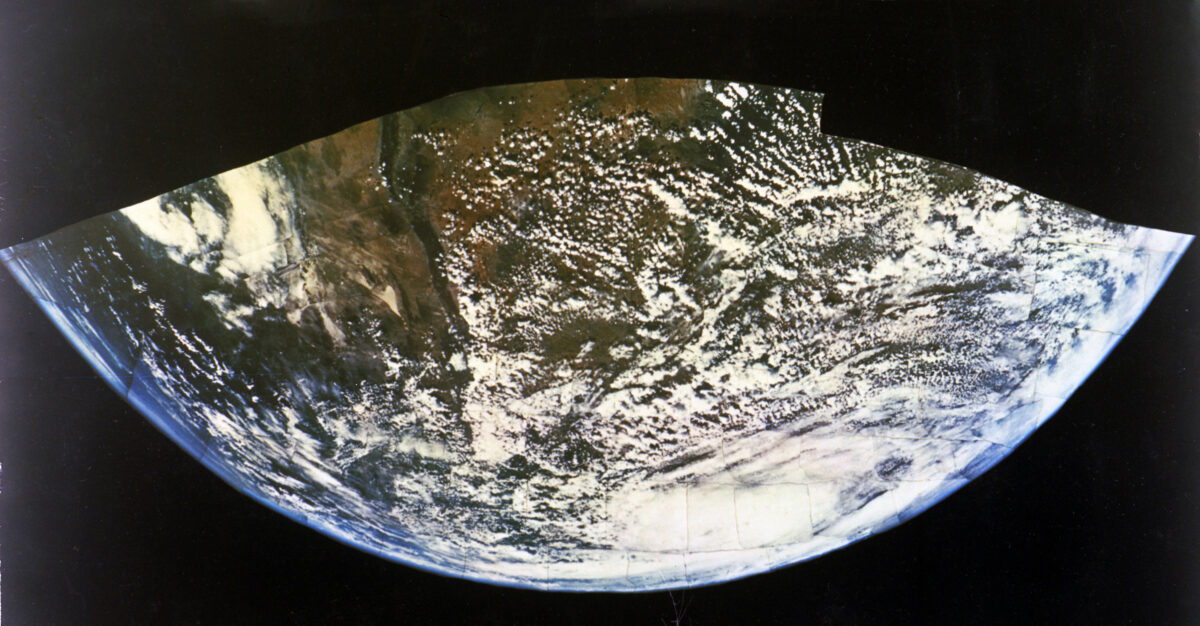

First Color Photo of Earth from Space (Part II):

The Mission & the Montage

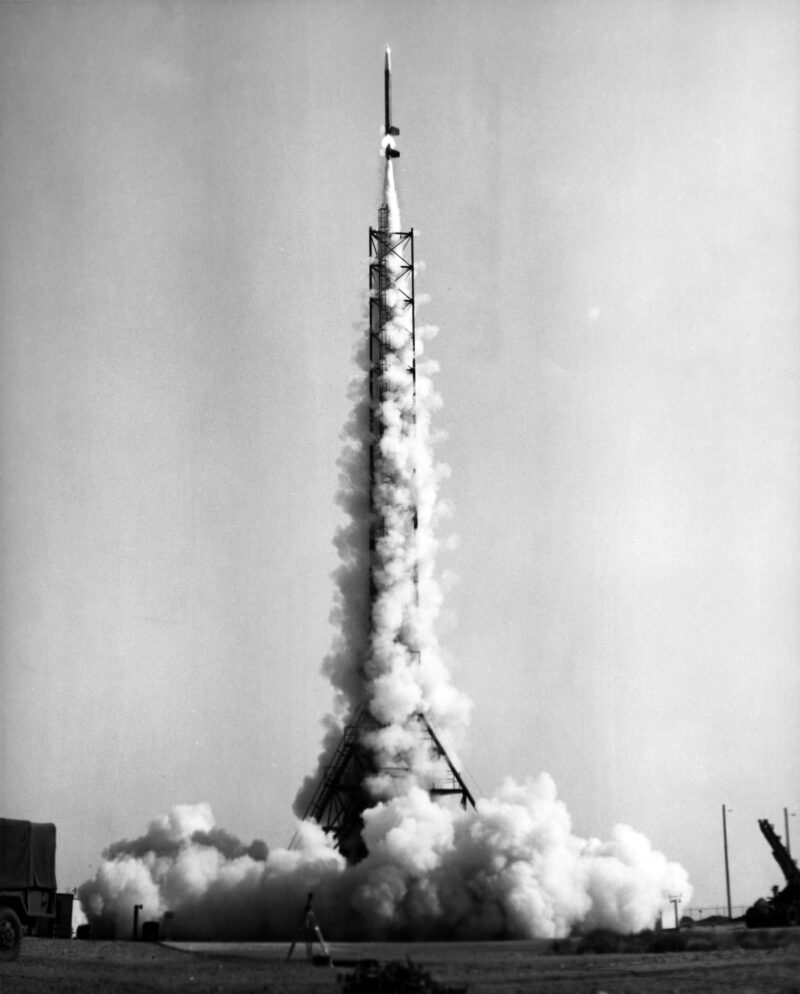

Aerobee Rocket AJ-10-24 carrying the first color film to record Earth from space with unidentified Navy personnel, October 1, 1954 (4 days before launch). Credit: Department of the Navy, courtesy White Sands Missile Range Museum

The story of the first color photographs of the Earth from space continues in Otto Berg’s own words, with light edits and editorial notes. The individual Earth photos appearing here (other than Berg’s original montage) were scanned and processed from the decades old internegatives that Otto Berg produced in order to create the Earth Montage in 1954. There was significant color fading of the negatives as compared with the 16mm film itself, which will be scanned as individual frames at the highest resolution available. For now, the images appearing here are the best versions of these images available, though when the 16mm film gets scanned and the images processed, better versions will replace those currently available.

THE 1954 MONTAGE OF PLANET EARTH – continued excerpts from Berg’s unpublished autobiography, “Confessions of a Rocket Scientist” (copyright Otto Berg, date unknown, excerpted with family permission) detailing the impetus and challenges behind capturing color photographs of Earth from space for the first time:

The Aerobee rocket used in this project was scheduled for an early morning launch. As I lay in bed the night before launch I suddenly realized that I had not refocused the camera for the vacuum conditions of the upper atmosphere. (the focal length has to be changed as a lens goes from atmospheric pressures to vacuum pressures due to a term called the ‘index of refraction’) I knew the project manager would not delay the launch simply to allow me to correct my neglect. A photographic experiment was not high priority! I lay awake scheming and dreaming up explanations for the 50 feet of “fuzzy” color film that would be recovered. However, as I went out to the launch site early in the morning, I was told that the rocket had developed a fuel leak during the night and all instruments would have to be removed while the launch team serviced the rocket! Wow! Another answered prayer! All that missed sleep and the ingenious explanations for naught. So, a new date for the launch was carried out.

The camera was housed in a heavy fiber-glass case to protect the film pack as the nose cone section hit the desert sand.

The rocket’s trajectory was not controlled once it emerged from the launching tower which tower merely served to give the rocket vertical direction and stability until its velocity was sufficient to provide aerodynamic stability and direction by the rocket’s fins plus the booster fins.

Aerobee Rocket Launch from White Sands Proving Grounds circa 1954-55. Courtesy White Sands Missile Range Museum

Typically, as an Aerobee rocket roars off it encounters an increasingly rarefied atmosphere. At approximately 25 miles above Earth, the atmosphere is so thin (not sufficiently dense) that the rocket fins are ineffective in the orientation of the rocket’s attitude relative to Earth’s surface. Accordingly, because there were no significant external forces, such as atmospheric density, to act upon its orientation, the normal Aerobee rocket would maintain its vertical orientation (relative to the Earth’s surface) past peak altitude and including a leg of its descent until its highspeed reentry plus an increased atmospheric density would cause it to violently reverse its vertical orientation, to again accommodate the fins. As a result of the violent reorientation, the normally behaving Aerobee would break up into 2 sections—the upper nose cone section and the lower fuel/rocket motor section. Both, sections, now aerodynamically unstable, would come tumbling through the atmosphere and impact upon the beautiful untouched New Mexico desert and scare the liver out of nearby rattlers and horned toads.

This rocket behaved quite differently, however, as though it had been programmed to favor a photographic covering of the Earth’s features. It flew like an arrow! [A]s it approached peak altitude of 100 miles its axis began tilting over much as an arrow would fly (if the arrow was within an atmosphere). Question! Was the trajectory Divinely controlled to provide the unusual resultant photo coverage? I think so.

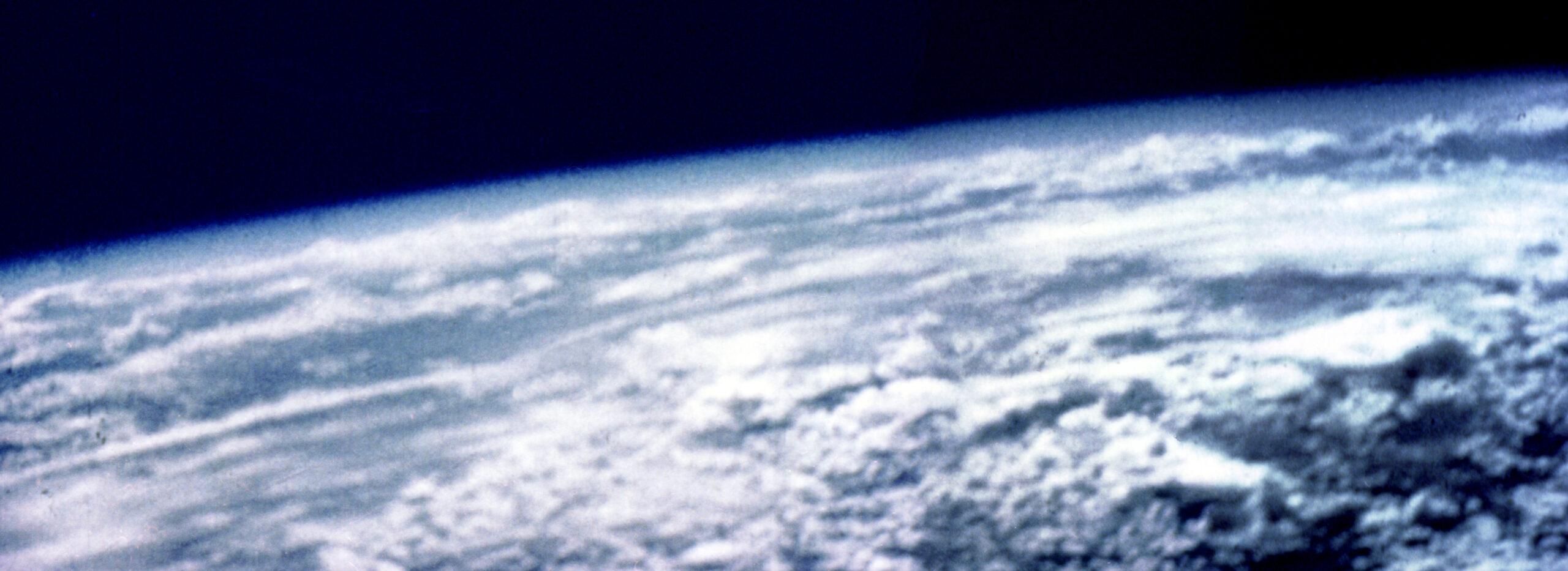

The result? As the slowly spinning rocket was also slowly tipping over from the vertical, the camera mounted in the side of the rocket and perpendicular to its axis, would alternately photograph a strip of terrain-starting at the horizon—and then a section of open space and then a lower strip of terrain etc. until about one-half of the portion of Planet Earth visible from a distance of 100 miles had been recorded on color film.

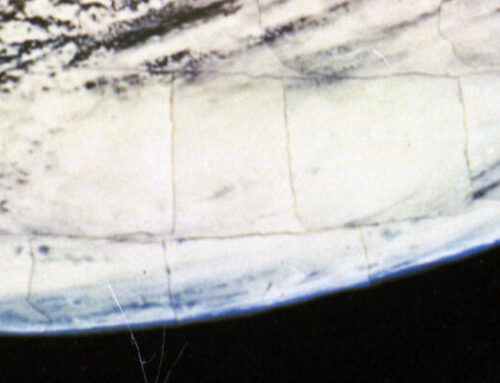

The successive strips of Earth’s terrain are clearly visible as one views the montage. They go from left to right as dictated by the spin of the rocket. Then the last frames of the final strip end in a fuzzy image as the 50 feet of 16 mm Kodachrome film are used up. If the camera had not run out of film, the entire sphere would have been recorded. However, the rocket was descending at an accelerated rate and the altitude of the rocket would rapidly be reducing causing giant distortions in any assembly of pictures.

[Note: Berg wrote this recollection some 50 years after making the Earth Montage and is mistaken on the film being used up in space. The camera started recording at 6 frames per second at the rocket’s peak altitude of 100 miles and continued recording for the duration of the flight. The nose cone of the Aerobee rocket detached and landed softly by parachute back at White Sands Proving Ground with the camera still recording all the way down, as the final frames of the film reveal. When Berg made the montage, he numbered the internegative film strips in reverse, that is, the later images the 16mm film recorded of the southern limb and horizon of the planet that Berg used for the montage were numbered strip #1, while the first images recorded on the 16mm film Berg labeled as strip #8 – which may explain why his recollection of the recording was reversed in this account].

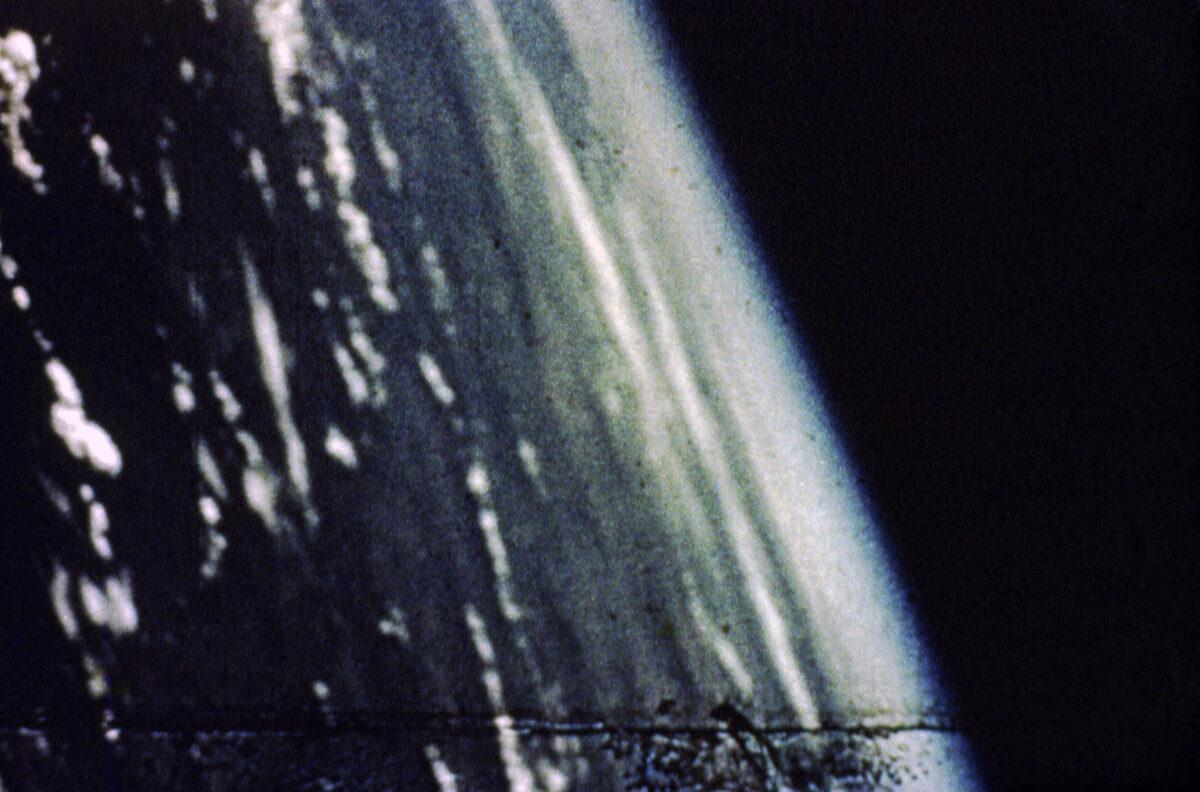

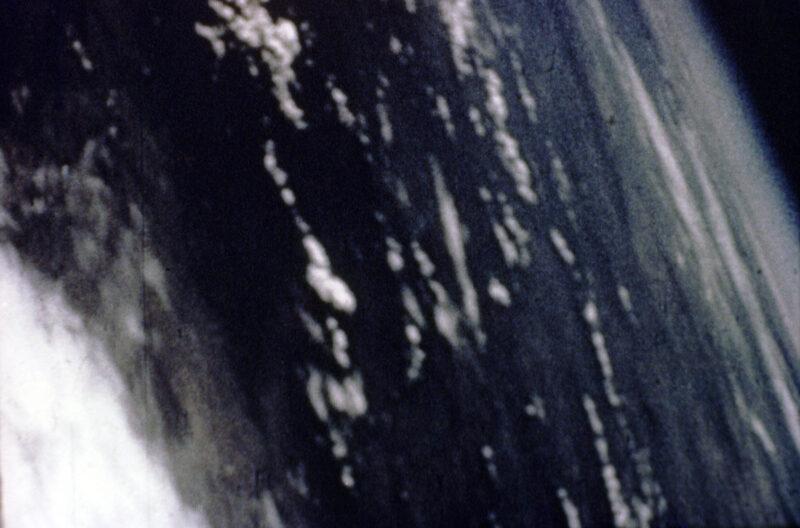

I very anxiously awaited post-flight recovery of the camera and film. When the color 16 mm movie film came back from processing, I was pleased to see that the exposure was essentially perfect. My first impression was to see the gradual photographic recording of the horizon in color and to see how it stood out in sharp contrast to the blackness of space as the Earth’s atmosphere ended.

Frame #21 of the NRL/Berg film showing the curvature of the Earth against the blackness of space in color for the first time

I decided to enlarge several 16 mm frames of horizon shots to see if the Earth’s curvature would be significant. Indeed, it was, so I enlarged/printed every 3rd 16 mm frame over a longer period of the flight and that also worked out well.

Finally, it dawned on me that possibly the entire 50 feet of Kodachrome movie film could be applied toward a large segment of Earth and showing a significant portion of Earth’s curvature. I asked the photography department to print up every third movie frame to a print size, 3.5 inches by 5 inches. Then, somewhat to the dismay of my Wife, I spread out the approximately 400 prints on our dining room table and began the puzzle of matching clouds, cloud shadows, terrain, and horizons together.

I could easily calculate the anticipated diameter of the puzzle which greatly helped to organize the horizon shots. Eventually, I had assembled about 140 prints into the 3-foot by 4-foot montage of the Earth which now hangs in the Smithsonian Institute Air and Space Museum.

And there it was—this color montage of Planet Earth. I cannot say that I was at all excited about the product, except that it represented a photographic feat and a new record for revealing the Earth’s curvature. I guess I considered it comparable to having photographed a 3-legged chicken. My wife was even less impressed, but grateful to having regained the use and possession of her dining room table “for more useful purposes”. I remember being impressed with the observation that every cloud had a corresponding shadow of itself on the ground. The huge glob of white cloud that later was identified as a small hurricane over Texas, didn’t register as important at all.

In the above image of Earth, south is at the bottom. The 16mm camera aboard the Aerobee rocket first began recording at the top of the image above, with the first “strip” described by Berg consisting of 21 frames going from right to left in the above image. This corresponds with the first 21 frames recorded on the 16mm film. The first image recorded with the horizon and curvature of the Earth as seen against black space are visible in frames 20-21. Berg selected successive frame “strips” as the angle of the camera moved successively further south as the rocket spun in space, recording alternating strips of Earth and strips of black space with each spin until the rocket and camera descended back to earth.

The actual first color photograph of the Earth from space is primarily of clouds:

While the first color photograph of the horizon and curvature of the Earth against the blackness of space is the 20th frame of the 16 mm film:

Though in my opinion, frame #21 makes for a better “first color photo of Earth from space” photograph, though it is technically speaking the second image showing Earth’s horizon:

Next Time: More Useful Purposes